18 Can we live on renewables?

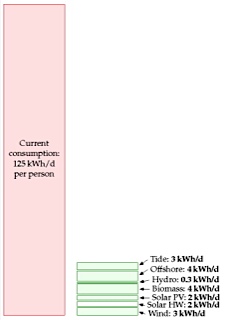

The red stack in figure 18.1 adds up to 195 kWh per day per person. The green stack adds up to about 180 kWh/d/p. A close race! But please remember: in calculating our production stack we threw all economic, social, and environmental constraints to the wind. Also, some of our green contributors are probably incompatible with each other: our photovoltaic panels and hot-water panels would clash with each other on roofs; and our solar photovoltaic farms using 5% of the country might compete with the energy crops with which we covered 75% of the country. If we were to lose just one of our bigger green contributors – for example, if we decided that deep offshore wind is not an option, or that panelling 5% of the country with photovoltaics at a cost of £200 000 per person is not on – then the production stack would no longer match the consumption stack.

Furthermore, even if our red consumption stack were lower than our green production stack, it would not necessarily mean our energy sums are adding up. You can’t power a TV with cat food, nor can you feed a cat from a wind turbine. Energy exists in different forms – chemical, electrical, kinetic, and heat, for example. For a sustainable energy plan to add up, we need both the forms and amounts of energy consumption and production to match up. Converting energy from one form to another – from chemical to electrical, as at a fossil-fuel power station, or from electrical to chemical, as in a factory making hydrogen from water – usually involves substantial losses of useful energy. We will come back to this important detail in Chapter 27, which will describe some energy plans that do add up.

Here we’ll reflect on our estimates of consumption and production, compare them with official averages and with other people’s estimates, and discuss how much power renewables could plausibly deliver in a country like Britain.

The questions we’ll address in this chapter are:

- Is the size of the red stack roughly correct? What is the average consumption of Britain? We’ll look at the official energy-consumption numbers for Britain and a few other countries.

- Have I been unfair to renewables, underestimating their potential? We’ll compare the estimates in the green stack with estimates published by organizations such as the Sustainable Development Commission, the Institution of Electrical Engineers, and the Centre for Alternative Technology.

- What happens to the green stack when we take into account social and economic constraints?

Red reflections

Our estimate of a typical affluent person’s consumption (figure 18.1) has reached 195 kWh per day. It is indeed true that many people use this much energy, and that many more aspire to such levels of consumption. The average American consumes about 250 kWh per day. If we all raised our standard of consumption to an average American level, the green production stack would definitely be dwarfed by the red consumption stack.

What about the average European and the average Brit? Average European consumption of “primary energy” (which means the energy contained in raw fuels, plus wind and hydroelectricity) is about 125 kWh per day per person. The UK average is also 125 kWh per day per person. 1

These official averages do not include two energy flows. First, the “embedded energy” in imported stuff (the energy expended in making the stuff) is not included at all. We estimated in Chapter 15 that the embedded energy in imported stuff is at least 40 kWh/d per person. Second, the official estimates of “primary energy consumption” include only industrial energy flows – things like fossil fuels and hydroelectricity – and don’t keep track of the natural embedded energy in food: energy that was originally harnessed by photosynthesis.

Another difference between the red stack we slapped together and the national total is that in most of the consumption chapters so far we tended to ignore the energy lost in converting energy from one form to another, and in transporting energy around. For example, the “car” estimate in Part I covered only the energy in the petrol, not the energy used at the oil refinery that makes the petrol, nor the energy used in trundling the oil and petrol from A to B. The national total accounts for all the energy, before any conversion losses. Conversion losses in fact account for about 22% of total national energy consumption. Most of these conversion losses happen at power stations. Losses in the electricity transmission network chuck away 1% of total national energy consumption. 2

When building our red stack, we tried to imagine how much energy a typical affluent person uses. Has this approach biased our perception of the importance of different activities? Let’s look at some official numbers. Figure 18.2 shows the breakdown of energy consumption by end use. The top two categories are transport and heating (hot air and hot water). Those two categories also dominated the red stack in Part I. Good.

Road transport

Petroleum

22.5

Railways

Petroleum

0.4

Water transport

Petroleum

1.0

Aviation

Petroleum

7.4

All modes

Electricity

0.4

All energy used by transport

31.6

Table 18.3. 2006 breakdown of energy consumption by transport mode, in kWh/d per person. Source: Dept. for Transport (2007).Figure 18.4. Power consumption per capita, versus GDP per capita, in purchasing-power-parity US dollars. Squares show countries having "high human development;" circles, "medium" or "low." [Figure 30.1](../Text/chap30.xhtml#fig30.1) shows the same data on logarithmic scales. [^3]Let’s look more closely at transport. In our red stack, we found that the energy footprints of driving a car 50 km per day and of flying to Cape Town once per year are roughly equal. Table 18.3 shows the relative importances of the different transport modes in the national balance-sheet. In the national averages, aviation is smaller than road transport.

How do Britain’s official consumption figures compare with those of other countries? Figure 18.4 shows the power consumptions of lots of countries or regions, versus their gross domestic products (GDPs). There’s an evident correlation between power consumption and GDP: the higher a country’s GDP (per capita), the more power it consumes per capita. The UK is a fairly typical high-GDP country, surrounded by Germany, France, Japan, Austria, Ireland, Switzerland, and Denmark. The only notable exception to the rule “big GDP implies big power consumption” is Hong Kong. Hong Kong’s GDP per capita is about the same as Britain’s, but Hong Kong’s power consumption is about 80 kWh/d/p.

The message I take from these country comparisons is that the UK is a fairly typical European country, and therefore provides a good case study for asking the question “How can a country with a high quality of life get its energy sustainably?”

Green reflections

People often say that Britain has plenty of renewables. Have I been mean to green? Are my numbers a load of rubbish? Have I underestimated sustainable production? Let’s compare my green numbers first with several estimates found in the Sustainable Development Commission’s publication The role of nuclear power in a low carbon economy. Reducing CO2 emissions – nuclear and the alternatives. Remarkably, even though the Sustainable Development Commission’s take on sustainable resources is very positive (“We have huge tidal, wave, biomass and solar resources”), all the estimates in the Sustainable Development Commission’s document are smaller than mine! (To be precise, all the estimates of the renewables total are smaller than my total.) The Sustainable Development Commission’s publication gives estimates from four sources detailed below (IEE, Tyndall, IAG, and PIU). Figure 18.6 shows my estimates alongside numbers from these four sources and numbers from the Centre for Alternative Technology (CAT). Here’s a description of each source.

- IEE The Institute of Electrical Engineers published a report on renewable energy in 2002 – a summary of possible contributions from renewables in the UK. The second column of figure 18.6 shows the “technical potential” of a variety of renewable technologies for UK electricity generation – “an upper limit that is unlikely ever to be exceeded even with quite dramatic changes in the structure of our society and economy.” According to the IEE, the total of all renewables’ technical potential is about 27 kWh/d per person.

- Tyndall The Tyndall Centre’s estimate of the total practicable renewable energy resource is 15 kWh per day per person.

- IAG The Interdepartmental Analysts Group’s estimates of renewables, take into account economic constraints. Their total practical and economical resource (at a retail price of 7p/kWh) is 12 kWh per day per person.

- PIU The “PIU” column shows the “indicative resource potential for renewable electricity generation options” from the DTI’s contribution to the PIU review in 2001. For each technology I show their “practical maximum,” or, if no practical maximum was given, their “theoretical maximum.”

- CAT The final column shows the numbers from the Centre for Alternative Technology’s “Island Britain” plan Helweg-Larsen and Bull (2007).

Bio-powered Europe

Sometimes people ask me “surely we used to live on renewables just fine, before the Industrial Revolution?” Yes, but don’t forget that two things were different then: lifestyles, and population densities.

Turning the clock back more than 400 years, Europe lived almost entirely on sustainable sources: mainly wood and crops, augmented by a little wind power, tidal power, and water power. It’s been estimated that the average person’s lifestyle consumed a power of 20 kWh per day. 4 The wood used per person was 4 kg per day, which required 1 hectare (10 000 m2) of forest per person. The area of land per person in Europe in the 1700s was 52 000 m2. In the regions with highest population density, the area per person was 17 500 m2 of arable land, pastures, and woods. Today the area of Britain per person is just 4000 m2, so even if we reverted to the lifestyle of the Middle Ages and completely forested the country, we could no longer live sustainably here. Our population density is far too high.

Green ambitions meet social reality

Figure 18.7 is bleak news. Yes, technically, Britain has “huge” renewables. But realistically, I don’t think Britain can live on its own renewables – at least not the way we currently live. I am partly driven to this conclusion by the chorus of opposition that greets any major renewable energy proposal. People love renewable energy, unless it is bigger than a figleaf. If the British are good at one thing, it’s saying “no.”

| Wind farms? | "No, they’re ugly noisy things." |

| Solar panels on roofs? | "No, they would spoil the visual amenity of the street." |

| More forestry? | "No, it ruins the countryside." |

| Waste incineration? | "No, I’m worried about health risks, traffic congestion, dust and noise." |

| Hydroelectricity? | "Yes, but not big hydro – that harms the environment." |

| Offshore wind? | "No, I’m more worried about the ugly powerlines coming ashore than I was about a Nazi invasion." [5] |

| Wave or geothermal power? | "No, far too expensive." |

After the public consultation. I fear the maximum Britain would ever get from renewables is in the ballpark of 18kWh/d per person. (The left-hand consumption number, 125kWh/d per person, by the way, is the average British consumption, excluding imports, and ignoring solar energy acquired through food production.)

After all these objections, I fear that the maximum Britain would ever get from renewables would be something like what’s shown in the bottom right of figure 18.7.

Figure 18.8 offers guidance to anyone trying to erect wind farms in Britain. On a map of the British mainland I’ve shown in white a 2-km radius exclusion zone surrounding every hamlet, village, and town. These white areas would presumably be excluded from wind-farm development because they are too close to the humans. I’ve coloured in black all regions

that are more than 2 km from any human settlement. These areas are largely excluded from wind-farm development because they are tranquil, and it’s essential to protect tranquil places from industrialization. If you want to avoid objections to your wind farm, pick any piece of land that is not coloured black or white.

Some of these environmentalists who have good hearts but confused minds are almost a barrier to tackling climate change.

Malcolm Wicks, Minister of State for Energy

We are drawing to the close of Part I. The assumption was that we want to get off fossil fuels, for one or more of the reasons listed in Chapter 1 – climate change, security of supply, and so forth. Figure 18.9 shows how much power we currently get from renewables and nuclear. They amount to just 4% of our total power consumption.

The two conclusions we can draw from Part I are:

To make a difference, renewable facilities have to be country-sized.

For any renewable facility to make a contribution comparable to our current consumption, it has to be country-sized. To get a big contribution from wind, we used wind farms with the area of Wales. To get a big contribution from solar photovoltaics, we required half the area of Wales. To get a big contribution from waves, we imagined wave farms covering 500 km of coastline. To make energy crops with a big contribution, we took 75% of the whole country.

Renewable facilities have to be country-sized because all renewables are so diffuse. Table 18.10 summarizes most of the powers-per-unit-area that we encountered in Part I.

To sustain Britain’s lifestyle on its renewables alone would be very difficult. A renewable-based energy solution will necessarily be large and intrusive.

It’s not going to be easy to make a plan that adds up using renewables alone. If we are serious about getting off fossil fuels, Brits are going to have to learn to start saying “yes” to something. Indeed to several somethings.

In Part II I’ll ask, “assuming that we can’t get production from renewables to add up to our current consumption, what are the other options?”

Power per unit land or water area

Wind

2 W/m2

Offshore wind

3 W/m2

Tidal pools

3 W/m2

Tidal stream

6 W/m2

Solar PV panels

5-20 W/m2

Plants

0.5 W/m2

Rain-water (highlands)

0.24 W/m2

Hydroelectric facility

11 W/m2

Geothermal

0.017 W/m2

Table 18.10. Renewable facilities have to be country-sized because all renewables are so diffuse.Notes and further reading

- UK average energy consumption is 125 kWh per day per person. I took this number from the UNDP Human Development Report, 2007. The DTI (now known as DBERR) publishes a Digest of United Kingdom Energy Statistics every year. [uzek2]. In 2006, according to DUKES, total primary energy demand was 244 million tons of oil equivalent, which corresponds to 130 kWh per day per person. I don’t know the reason for the small difference between the UNDP number and the DUKES number, but I can explain why I chose the slightly lower number. As I mentioned in chapter 2, DUKES uses the same energy-summing convention as me, declaring one kWh of chemical energy to be equal to one kWh of electricity. But there’s one minor exception: DUKES defines the “primary energy” produced in nuclear power stations to be the thermal energy, which in 2006 was 9 kWh/d/p; this was converted (with 38% efficiency) to 3.4 kWh/d/p of supplied electricity; in my accounts, I’ve focused on the electricity produced by hydroelectricity, other renewables, and nuclear power; this small switch in convention reduces the nuclear contribution by about 5 kWh/d/p.↩

- Losses in the electricity transmission network chuck away 1% of total national energy consumption. To put it another way, the losses are 8% of the electricity generated. This 8% loss can be broken down: roughly 1.5% is lost in the long-distance high-voltage system, and 6% in the local public supply system. Source: MacLeay et al. (2007).↩

- In the Middle Ages, the average person’s lifestyle consumed a power of 20 kWh per day. Source: Malanima (2006).↩